The Full Cost Project aims to shift the focus from overhead to outcomes and what good outcomes really cost. Simply put, the full cost includes all necessary costs for a nonprofit organization to deliver on mission and to be sustainable over the long term. Like any enterprise (think of for-profit corporations), nonprofits and social enterprises must be able to cover the whole cost of their programs and operations if they are to deliver excellent outcomes over time. Whether an organization is serving returning veterans, providing health and human services to the most needy, or building vibrant communities, the cost of delivering results includes not only direct programmatic expenses but also the capacity and capital needs of the organization.

Misguided policies are not the only factor driving the low ceilings on overhead; culture and behavior tend to play an even bigger role. Cost decisions are drawn from many different sources and individuals in an organization; some costs make the cut and others don’t. The formula varies from one funder to another, and sometimes from one program officer to another within the same grantmaking organization. The Full Cost approach helps to overcome these inconsistencies and better aligns the missions of nonprofits with the funders who support them.

The Overhead Question

|

There has been much written on the idea of nonprofit overhead and whether or not it is a good indicator of nonprofit effectiveness. Our aim here is not to rehash old arguments around the overhead question. In fact, we believe we need to move beyond the overhead question and adopt a new approach that shifts the focus of grantmaking from inputs (overhead costs) to funding social outcomes.

One of the biggest challenges around funding for nonprofit overhead is that there is no consistent definition of “overhead” – in fact the term ‘overhead’ is not an official accounting term. To make it more confusing, you may also hear terms such as ‘indirect costs’, ‘administrative costs’, or ‘shared costs’ being used as the equivalent of ‘overhead’.

In the for-profit world, the customer buys the product and pays the fully loaded cost for that product. For example, when you go into your local coffee shop, you don’t restrict how much of your payment can be used to cover overhead or indirect costs. In an article in the Seattle Times, writer Melissa Allison provides a breakdown of the direct costs, indirect costs and profits for a small latte. She shows that only 25%-30% of the price you pay is for direct costs while the rest of your payment goes to cover marketing, administrative, and operating costs along with profits for the coffee shop.

Millions of people have no problem walking into their local coffee shop every morning and paying the fully loaded cost for their latte. However, when it comes to funding organizations working with the homeless, disabled veterans, or children in foster care, these same donors want to limit how much the nonprofit organization can spend on infrastructure and operational support. How long would any for-profit business last if its customers limited the amount of money the company could spend on overhead, operations and profits? Probably not very long. Yet we expect nonprofit and social sector organizations to achieve great outcomes while we continue to starve their organization’s infrastructure and operational needs. Clearly we need a new approach. If we want impact and great outcomes, then we need to begin with an approach that starts with the outcomes in mind, understands what those outcomes really cost and determines what role funders want their money to play.

The Full Cost of Great Outcomes

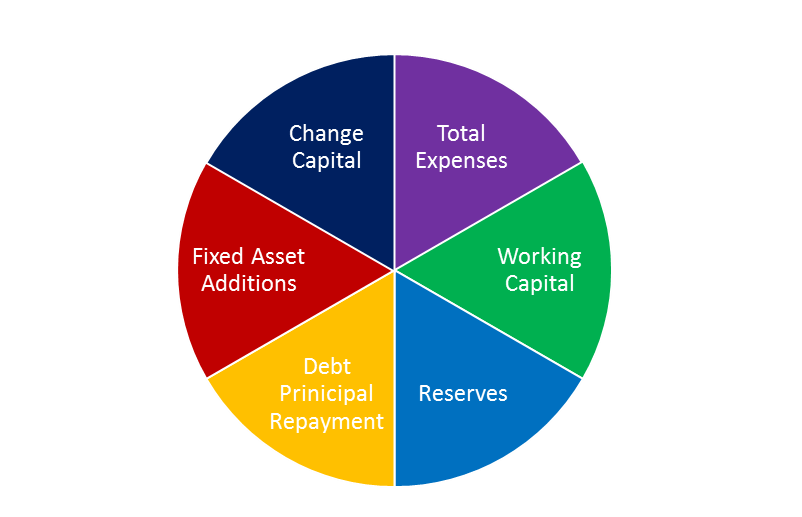

As defined by the Nonprofit Finance Fund, the full cost of delivering outcomes includes six key elements: Total Expenses, Working Capital, Reserves, Debt Principal Repayment, Fixed Asset Additions, and Change Capital.

Total Expenses

Total expenses are the day-to-day expenses of running your organization. They include:

- Regular or recurring expenses (i.e. salaries, Phone bill, program supplies)

- One-time or extraordinary expenses (i.e. legal fees to defend a law suit, or the cost of launching a capital campaign)

- Depreciation, which is a non-cash expense that estimates the decreasing value of your fixed assets (e.g. building, vehicles, computers) over time until they are expected to need replacement

- Upfront and ongoing cost of impact measurement

- “Direct” program expenses

- “Indirect” or “overhead” expenses

- Unfunded Expenses

Unfunded expenses are those expenses that are not currently incurred, but, if covered, would allow your organization to work at its current level in a way that is reasonable and fair. One common example in the nonprofit sector is overworking and underpaying staff.

Example: An Executive Director works 60 hours per week. The organization should hire a part time assistant, so the Executive Director can reduce her hours to 40 hours per week (without taking a pay cut). The salary of the assistant would be the unfunded expenses.

Other examples of unfunded expenses include making due with outdated software, slow internet, or sub-par supplies.

Unfunded expenses are NOT associated with expanding or doing more; they support what is already being done by your organization.

The income statement reflects total expenses, with the exception of unfunded expenses. Unfunded expenses are not captured in financial reports

Total Expenses do NOT include:

- Any purchase that is capitalized, such as a building or equipment; such purchases are captured in Fixed Asset Additions (see below)

- Repaying debt principal; this lives in Debt Principal Repayment (see below)

Working Capital

Working capital is the dollars to cover the predictable timing of cash ebbs and flows in the normal course of business. Organizations with sufficient working capital are able to pay bills on time, even during months when there are no cash receipts.

Working capitals is needed by all organizations. It should be easily accessible to management, without restrictions or strict designation. Working capital dollars are usually held in the organization’s main checking account.

The amount of working capital needed is highly variable from organization to organization, as it depends on the unique timing of cash in-flows and out-flows within each nonprofit. Some organizations have minimal gaps between cash in-flows and out-flows. Less than one month of working capital may be sufficient for them. Others have very large gaps between cash in-flows and out-flows. They may need to have 11 months of working capital at their cash high point in the year to make it through their cash low point in the year.

Securing a line of credit from a bank or credit union is one way to manage cash flow. The line of credit can be used to increase working capital during cash low points, and repaid during cash high points. Banks will rarely extend new lines of credit when cash is at a low point. Organizations should establish a line of credit “when they don’t need it” so it is available when they do.

Working capital is NOT meant to cover lost revenue, pay for annual deficits, or continue unsustainable activity.

Reserves

Reserves are savings that mitigate risk for the organization – whether that be the risk inherent in your funding streams, the risk of trying something new, or the risk that something may go wrong with your building or equipment.

Reserves are needed by all organizations, but the size and purpose vary – there is no one-size-fits-all.

Common examples of reserves:

- Operating reserve: To protect the organization from short-term risk (e.g. lost funding, unexpected expense, leadership transition) or pursue opportunity

- Facilities reserve: To maintain fixed assets and pay for repairs and/or replacement (e.g. building, equipment, etc.)

- Research and development reserve: To allow for experimentation, risk-taking, trial and error; to investigate a new program or approach

- Investment reserve: To generate revenue through investment vehicles

You can name and define reserves for your organization in a way that best supports your mission and vision. An operating reserve is often a good first priority when it comes to reserves. It is possible to have a single reserve that can serve multiple purposes. For example, you could have an operating reserve that can also be used for research and development of new programs. However, you should carefully define the criteria of the reserve and the amounts needed for different purposes. One aggregated reserve can give a false impression that resources are adequate to meet your needs.

Reserves should be accessible to management depending on the immediacy of need. Some may be board-designated and require board approval to spend. They may be held as cash in a bank account or as investments that can be liquidated in a reasonable timeframe. Most reserves are intended to be replenished once they have been used.

Debt Principal Repayment

Debt principal repayment are the dollars to pay down debt (e.g. line of credit, mortgage, loans, other forms of borrowing, etc.).

Debt can be a valuable financing tool if used strategically. It may seem obvious that when you borrow money, you need a plan to pay it back. But the structure of financial reporting can obscure debt repayment. If an organization makes a monthly mortgage payment, the principal reduction does not appear on the income statement (or P&L) as an expense. Only the interest appears as an expense. Instead, principal repayment appears on the organization’s statement of financial position (or balance sheet) as a reduction in cash and a reduction in the mortgage principal due. In other words: repayment is commonly financed through year-over-year surpluses.

Consider how quickly your organization’s existing or planned debt needs to be repaid.

Fixed Asset Additions

Fixed asset additions are the dollars to purchase new equipment, buildings, furniture, land, leaseholder improvements or other fixed assets. Fixed asset additions are NOT replacement or simple maintenance of existing fixed assets (this lives in a reserve) or small equipment purchases that are expensed.

Change Capital

Change capital is a large, periodic, investment into an organization to change the business model in a significant way (e.g. the size or reach of mission and/or how you make and spend money). Change capital should be large enough to cover up-front costs of change and deficits incurred until the change is complete, when ideally the new business model revenue exceeds the new expenses. For this reason, change capital should nearly always include adequate funds for the launch or scaling of contributed or earned revenue generating activities.

Change capital that seeks to scale programs, but does not invest in revenue generating activities, will result in short-term program expansion, followed by program contraction when the change capital runs out. This is an improper structuring of change capital.

Change capital typically comes from an external source and is ideally large, flexible, and multi-year. Capital campaigns are one way to raise change capital dollars. Change capital is not often sourced through saving year-over-year surpluses.

Once an organization has received an infusion of change capital, we would not expect them to need change capital again for a long time: 10, 20, or even 30 years! The total amount of change capital needed can be difficult to calculate, because it is based on future projections of how the change will roll out, including how quickly new or expanded sources of revenue will be generated.

Full Cost Definitions and Images Copyrighted by Nonprofit Finance Fund